In late April of this year, 125 Paterson cops joined thousands of state and local employees in New Jersey to receive pink slips in the last year.

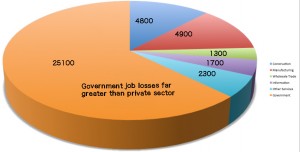

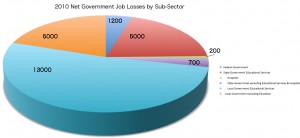

In the last twelve months, New Jersey has let go of over 26,000 state and local government workers. The Garden State is one of many states letting public sector employees go to balance their recession-battered budgets. The outspoken governor Chris Christie has drawn national attention for, as he bragged on television once, leading the nation in public sector layoffs by percentage.

In today’s labor market, laid-off workers in once-stable public sector jobs such as police officers and public school teachers face significant obstacles to rejoining the labor force because their skills are mostly relevant to their former positions.

Teachers are falling victim to budget cuts. With white-collar private sector jobs in high demand, laid-off teachers have a great deal of trouble finding work.

“I go on Career Builder all the time,” says Jennifer Marie Torre, a former high school English teacher in Newark who was laid off one year ago. Since then she has been collecting unemployment and living with family members. “I’m looking for jobs in writing, editing and publishing. I’ve also thought about changing careers completely or going to school for something else completely.”

Torre is also looking for jobs out of state, but is dismayed to learn that other cities where she would like to live are also cutting teaching staff. Even if she could find a job outside of New Jersey, she would have to be re-certified.

Teachers have skills that police don’t have, and they often have advanced degrees in pedagogy. “Economist Robert Brusca of FAO Economics says that they should have less trouble than most.

“Teachers have education, they went to college, they have degrees. Their jobs have complex sets of skills,” he says. “A math teacher understands math and might be able to find an even higher-paying job with those skills. Teachers can use their skills in a wide variety of occupations.”

A high level of education, however, has been a liability for some laid-off teachers such as Torre.

“I got my masters in English education,” she says. “I feel like I am overeducated for so many jobs. Some job listings say that a bachelors degree is preferred.”

“It was really discouraging to know that I put all this work into what I was doing and because of budget cuts I lost it,” she says.

Police in municipalities across the state, especially in high-crime cities such as Camden, Newark and Paterson, have been laid off police. According to the New Jersey Police Brotherhood Association, the state as a whole has had a net loss of 3100 officers in the past 20 months. 762 of those police jobs were lost to layoffs and the rest were lost when officers retired and were not replaced by younger recruits.

View New Jersey Police Layoffs in a larger map

The city of Newark laid off the last two graduating classes of their police academy in November, 2010. In all, 162 officers, 13% of the city’s total force was laid off at once.

“They hired these guys knowing that this budget crisis was coming and then just pulled from under them,” says Jim Stewart, Vice President of Newark’s police union. Stewart points out that these officers are expected to pay their way through police academy and supply their own uniforms.

“These guys were just used,” he said. “Cops do what they do because they are called to it. It’s not just another job.”

Many of those 162 officers are still unemployed because the entire state is shedding police jobs. When Newark announced the cuts in their force, police departments in Atlanta, Nashville, Norfolk, and Raleigh recruited some of the laid-off officers, but many of them are not prepared to leave their homes to find work.

Experts see police experience as even more difficult to translate into a private sector opportunity.

“Police are very different. There are private sector security jobs but a security guard isn’t quite the same,” says John Challenger, the CEO of an outplacement company.

Still, states and municipalities have a mandate to balance their budgets.

“This isn’t a zero sum game,” says Andrew Biggs, a resident scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “If they didn’t lay off public employees, there would be cuts in something else.”